– By Kumkum Pareek Malik

This article is an introduction to the field of Mind-Body Medicine, also called Integrative Medicine. A comprehensive study of the field is beyond the scope of this article. To explore the nuanced complexities of this subject, interested readers are encouraged to explore the field in more detail.

“Illness is a universal experience. There is no privilege that can make us immune to its touch.” (Larry Dossey, MD).

Mind Body medicine is a specialization at the intersection of biology, psychology, psychoneuroimmunology, sociology and behavioral genetics. Today it enjoys widespread acceptance in leading teaching hospitals, but its road has been a rocky one. Historically, this has been the case with most groundbreaking approaches that challenge existing ‘truths.’

In the 19th century, the medical community dismissed the view that individual diseases were caused by individual microscopic entities. The argument against germ theory was that these germs could not be seen; they were invisible to the naked eye, and made people feel helpless. In 1884, when the cholera epidemic hit Europe and the United States, the claim of Robert Koch that he had identified the microbe that caused cholera was attacked with hostility and dismissed.

For decades, the case was similar for Mind Body medicine. Well-intentioned scientists refused to accept that science may not have the tools or the mind set for asking the right questions about mind-body medicine. Thus, the fact that fifty percent of patients get well on placebo was dissmissed as ‘it’s just their mind making them believe they are getting the medicine.’ It took curiosity and humility for the right question to emerge: if the mind is so powerful that it can lead to the same results as medicines, what is going on?

Mind-Body medicine is based on a rationale quite different from that of allopathic medicine: it argues for the interconnections between systems which are otherwise seen as discrete and separate; for example the now proven connections between the central nervous system and the immune system, the cardiac system and the respiratory system or the much more complex interconnections between the digestive system and many other systems of the body including the central nervous system and the autonomic nervous system (these interconnections have led to the establishment of another nervous system of the brain, separate from the central and autonomic, called the enteric nervous system).

Indeed, so interwoven are these connections between the different systems of our brain and body that many leading medical schools (for example UPENN Medical School) no longer teach medicine based upon the discrete system approach. Instead, they treat the body as an interconnected system, with the brain an essential part of the body itself. Therefore, neurologically, chemically and functionally, it no longer makes any sense to treat each system as a discrete functional entity. It also makes no sense to treat the body and the brain as separate entities. Interconnectedness is a fact.

Mind Body medicine takes a neuro-bio-psycho-social approach to illness, especially illness prevention and management. As mentioned above, it brings together research from a number of disciplines. It has provided excellent research based approaches that have shown great potential for improving the quality of life, and of reducing the pain and difficulty of symptoms for people with various chronic symptoms. These approaches may even help to control or reverse certain underlying disease processes (Goldman, Gurin, 1993). The present thrust of research is to consider how the advances in neuro-bio-psycho-social research can be used to discover the true complexity of links between psychological, biological and social processes in illness.

This has direct implications for those of us who may wonder: okay, so what does all of this mean for me? It means that the way a doctor views your illness varies with that doctor’s approach to illness itself. When my husband had a quadruple coronary bypass, he asked his surgeon at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, MA, about the research behind the use of relaxation based imagery for better healing. Imagine his surprise when the surgeon not only endorsed it, but also recommended that he begin a mind-body based practice after surgery, such as yoga, for managing the bio-psycho-social factors that are related to coronary disease (in this case, the interactions between stress, high cholesterol, diabetes and coronary disease).

Mind body medicine argues that when illness strikes, treating only one system (the affected one) may not be enough. It goes even further, stating that deficits in one system may cause malfunctions in another. For example stress, which is a response of the body-mind, not a symptom, operates through many systems.

But perhaps the most controversial claim of mind-body medicine is that thoughts and emotions (invisible to the naked eye and eluding the microscope) affect the manifestation, treatment and recurrence of many illnesses.

This is actually not as radical as it may sound. After all, everyone has thoughts, and everyone has emotions. It is another matter that we do not always consciously connect these with our behavior or with our body’s behavior (illness, after all, is also a behavior, albeit not in the traditional sense).

The challenge for mind-body medicine, however, has been to demonstrate that on the one hand, these thoughts and emotions can produce long lasting chemical changes in our body (psycho-social factors can affect neuro-bio-physiology); and on the other hand, to also show that our neuro-bio-physiology can be changed by inputting certain thoughts and emotions.

In other words, can the proponents of mind-body medicine demonstrate that there is a two way process? In order to do so they must demonstrate that our thoughts and emotions can make us ill, and also, cognitive and physiological biofeedback processes, when inputted into a person under carefully controlled conditions, can prevent, improve or treat illnesses.

The first part of this question has been proven beyond doubt. The father of this research is Hans Selye (1907-1982) who demonstrated that stress causes long term chemical changes in the body, including in the immune, adrenal and central nervous systems. When our thoughts and emotions are in an alarm state (when we perceive/make a judgment that we are in danger), we enter into what is called an “activation state” (fight or flight response). This response involves the respiratory, cardiac, digestive, muscular, and central nervous system, including information processing and decision making abilities. There are three stages of this activation, with the third stage leading to chronic illnesses.

Results for the second part of this equation are more murky. There is much good news and straight forward results that have been proven again and again. Just one example may be sufficient to make the point: Herbert Benson has demonstrated the consistency and repeatability of the results of the Relaxation Response. An interesting aside: when my mother heard me rave about these studies during my own training with Benson, she scoffed at our need for results…”isme kya nayi baat hai (what is so new about this), she said. “Yeh to humare yogi sadiyon se jaante hein” (our yogis have known this for centuries).

Benson’s results are a good example of the interconnections between systems. Simply put (the reader is encouraged to read The Relaxation Response and Beyond the Relaxation response by Herbert Benson for a more detailed explanation), the experimental subject is taught to breathe in a certain way. This breathing pattern evokes responses in the respiratory system (the breathing becomes deep, regular and rhythmic), the cardiovascular system (heart rate slows down, and blood flows to the extremities) the muscular system (muscle tension reduces and tight muscles relax), body temperature in the extremities rises, and there are changes in the endocrine system.

There are at least two remarkable facts about this seemingly simple exercise: all of these systems were considered to be automatic, beyond the control of conscious manipulation. This is no longer considered true. A simple act of consciously altering breathing patterns evoked a change in the respiratory system, which then led to a cascade effect in many other systems. Secondly, this research highlighted the intricate and far reaching interconnections between the systems.

For example, for the body temperature to rise in the extremities (as measured by small thermometers called thermooosters held in the fingertips), many systems must respond. Neural feedback loops (involving both central nervous system as well as the autonomic nervous system) must be activated to impact the hypothalamus, which in turn controls sensors that cause vasodilation (vascular and circulatory systems), and the endocrine system to secrete norepinephrine, epinephrine and thyroxine to increase heat.

These kinds of results, proving that certain kinds of inputs, when delivered in carefully consistent and controlled ways, can alter neuro-bio-physiology, are now well accepted. We can demonstrate for instance that psychotherapy changes the brain, such that the same stimulus no longer evokes the old response but instead, a different response in brain wave patterns can be observed. Similar results for brain changes have been found for meditation, and for many other inputs such as biofeedback. These inputs have also been demonstrated to correlate with physical health in carefully controlled studies.

Other results have been somewhat more murky, especially those involving the immune system. Robert Ader (1932-2011) is credited with the first studies that proved that the immune system can “learn.” As a result of this groundbreaking research, it is now well accepted that there are many inputs to the brain, including stress, that can alter the immune system’s functions, including inputs that lower it’s effectiveness, and others that raise it’s effectiveness.

But the dilemma has been the variation in these results across different groups, and across different immune system diseases. In other words, what works for one person or one disease may not work for another. Cancer is a good example. It is a complex disease, and in reality, researchers are unanimous in concluding that the “causes” of immune system dysfunction in cancer are too many to be responsive to one method of treatment. Some people have responded dramatically to alternative treatments, but we do not yet have any commonly accepted guidelines about who will benefit from such treatments, what are the most effective such treatments, and when these should be avoided.

In other words, illness on the one hand, and psychological and social factors on the other, are not simple, single variables. Causality for illness, as well as causality for the prevention and treatment of illness, involves integration of as many factors as make up the patients life experience. This includes the thoughts and emotions of that person. Thoughtful integration of these variables, rather than separation, is the only simple answer available today.

To sum up, Mind Body medicine is a well respected though still controversial field. It brings together research in many subjects that has altered our perception of illness, recovery, and prevention. All of these states are now accepted as complex rather than single variable phenomena that involve many systems in addition to the system that is manifesting the disease. All of these systems must be addressed in treating illness as well as in preventing it.

Perhaps most importantly for me as a psychologist, Mind-Body medicine is helping us to understand that human beings must be considered in all of their complexity. This includes their emotional well-being. Connections between thoughts, attitudes and emotions and illness have been researched for almost every condition, from asthma to diabetes, to insomnia to ulcers, to cancer and of course, heart disease.

For a detailed study, here are some resources to explore this fascinating field further:

- Mind Body Health; The effects of Attitudes, Emotions, and Relationships, by Hafen et.al.

- The Psychobiology of Mind-Body Healing: Rossi. Good resource to understand how information from our thoughts and emotions is “transduced” into information that the nervous system can chemically respond to.

- The Psychoneuroimmunology of Chronic Disease: Kendall-Tackett, Editor. Good for understanding the key role and mind body connections of psychological factors in diseases such as heart disease, diabetes, multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer’s, and autoimmune disorders.

“Lifestyle change programs — which focus on nutritional interventions, stress reduction, moderate exercise and the development of greater love, intimacy and emotional wellbeing — can mitigate and sometimes even reverse the progression of chronic disease.”

— Dean Ornish, MD

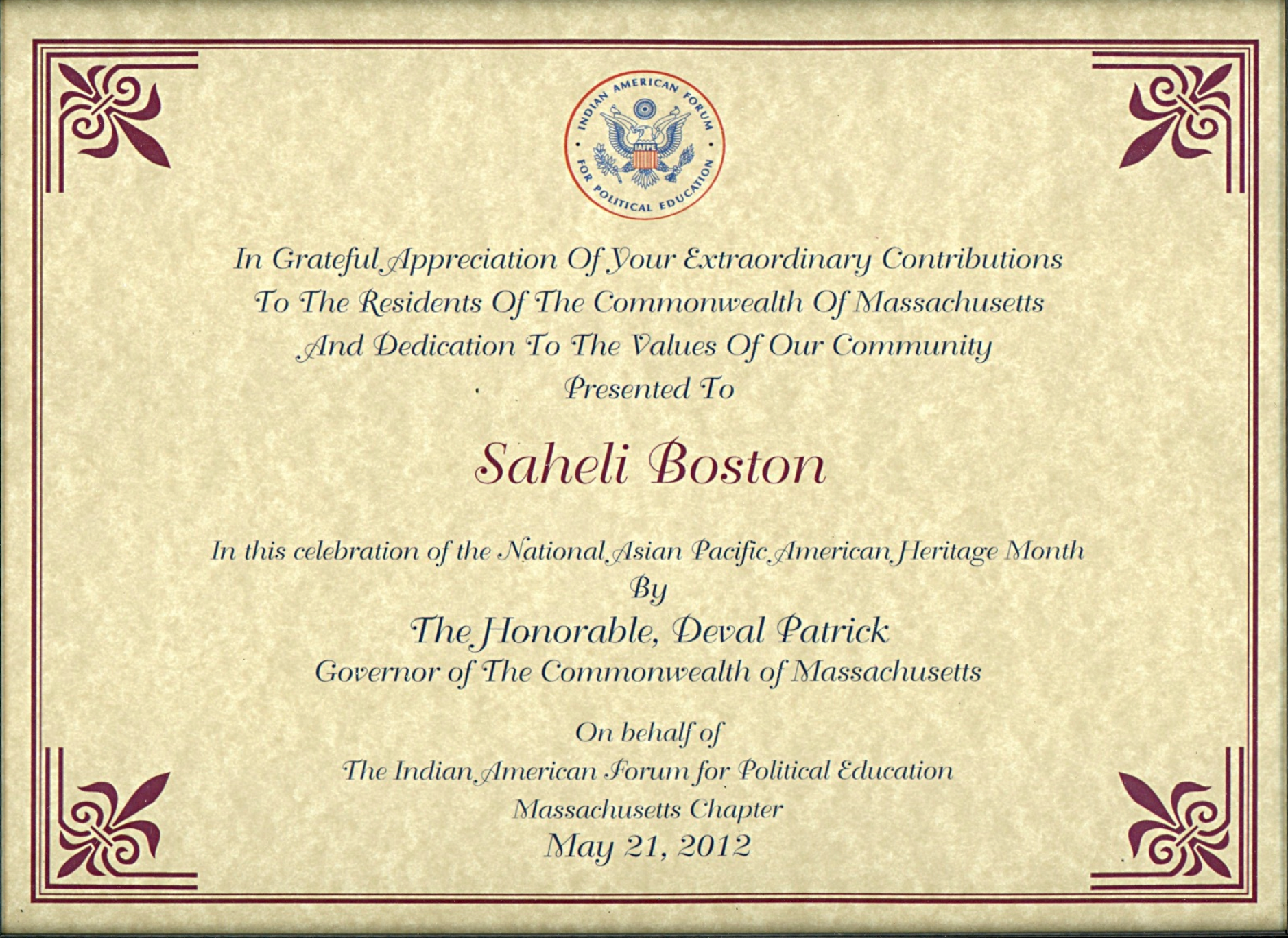

Saheli’s symposium on September 14, Raising Awareness about Emotional Well-Being, will host a one hour segment where practitioners from the following modalities will be available for the audience: Kundalini Yoga, Hypnotherapy, Acupuncture, Tai Chi, Qi Gong, Reiki, Reflexology, Healing with Sound: Crystal Bowls, and Ayurveda.

To learn more, please join Saheli’s Face Book Page: Emotional Well-Being Awareness Symposium